ANOTHER KIND OF LIFE

- Rebecca Otowa

- Apr 6, 2021

- 4 min read

Many places in Japan are regarded as romantic. One such place is the Gokayama Gassho villages in Toyama Prefecture, and the related Shirakawa-go in neighboring Gifu Prefecture. We visited two of the less famous ones last week on a car trip.

It’s a very isolated mountain area. The valleys are so steep that rice could not be grown in great quantities; the staple crops were kibi (a type of millet) and awa (a nut similar to chestnut). Animals were not kept, except horses for transport. The area gets a lot of snow in winter, usually about 2 meters.

The typical dwelling is called gassho (A-frame) style, and is thatched with reed. The ground floor is for living, with a big hearth and wellhead, and usually wooden floors; the upper area, under the steeply pitched roof with white paper-covered windows, was used for raising silkworms as an income generator. The other (secret) industry was producing saltpeter for use in gunpowder; the complicated fermentation process involved was carried out in hollowed-out areas under the floor. The reason for the secrecy was because these villages were under the power of the samurai Maeda Toshiie, who represented a threat to the Tokugawa government in the 17th century, and the gunpowder was given to him for his war effort in lieu of the usual rice tariff.

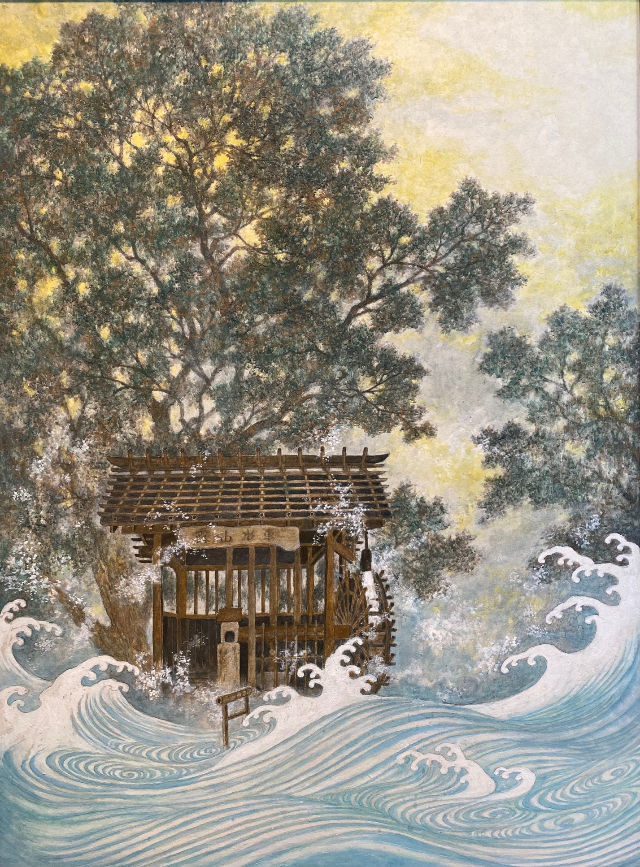

The villages had a small number of houses, and were isolated from each other by mountain peaks and a large, feisty river which had no bridges and was probably fordable in the proper season, but by no means all the time. From one season to the next, occupants would have seen no one but their neighbors, who were probably relatives.

Still, there was a rich cultural life, including festivals, songs and dances. The folk songs of the region are justifiably carefully preserved and famous in the world of such things. We bought a CD of folk songs to listen to as we drove through the steep mountain passes. It occurred to me that life in these villages, as in many parts of Japan before modern times, must have been a lonely one indeed.

One song, the Osayo-bushi, told from the point of view of a young girl named Osayo, has these lines:

Toge hosomichi namida de koete Weeping as I go over the mountain pass

Imawa oharade wabizumai My lonely life is now in the small meadow

Kokorobosoiyo taki noriwatari My heart is heavy as I cross the waterfall

Gokano sabishisa minishimiru The loneliness of Goka sinks into my bones

It’s easy to imagine. (You can see this song and the accompanying dance, performed as part of the Kokiriko Festival, on YouTube; search for it under Osayobushi).

The same faces every day; unrelenting work; battling the seasons; hunger; boredom as deep as the snow; married off to a man she does not love, and probably bullied by his family; the stink of fermentation rising from the floorboards; no wonder this girl cries in the last stanza, “I want to go home!”

The experience of visiting this place reminded me of the way human beings lived for century upon century, waking every day and putting bare feet on the cold floor, making a fire with wood that had been put ready the previous night, cooking the meager meal, looking outside at the grey clouds obscuring the mountaintop, listening to the voices of the river, snow runoff, and birds. Day after day after day. Births and deaths, festivals, growing a few flowers to vary the monotony.

Now we find the scene romantic, the blue snow scene with the little V-shaped houses dotted about; but I am guessing there was nothing romantic about these people’s lives as they were lived at the time. What would they have thought of us and our First World problems? “The cord of my phone charger doesn’t reach to the bed. I was treated off-handedly by the mechanic who fixed my flat tire. The local supermarket doesn’t have my favorite brand of potato chips.”

Most of all, extolling the virtues of such a place, with its remote beauty, and making it into a tourist destination, shows that deep down there is a part of us, in among our comfort and plethora of choices, that longs for the hardness and simplicity of that kind of life, and even wants to experience it for some limited time. Recently, younger people, either originally from here or from elsewhere, opt to live in these villages, fix up the old houses so they are more comfortable, make a parking pad for their cars. They may run a pension or a backpackers’ shelter, open little cafes and offer hot coffee with handmade buckwheat noodles flavored with spring greens that used to make the difference between survival and starvation. In front of the cafes are shelves with straw hats, baskets, maybe a traditional musical instrument or two, little objects fashioned out of wood or felt, scale models of the houses with manga characters depicted as living inside. The local governments operate groups for the preservation of folk songs and dances, subsidize rebuilding the thatched roofs, set up parking lots and information huts for the tourists.

These villages have taken on a new lease of life, one that the original occupants would never have foreseen. I’m glad that they survive, even in this way. The Gokayama gassho houses are famous throughout the world; they are Important Cultural Properties. I guess it’s all right that they are seen as romantic. At least they are seen.

This post reminds me of the history/reality shows I've been watching lately on YouTube. The premise of many of them is to dispel romantic notions of what life used to be like, so they make people try to live like long-ago people: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZUdOXhYwrgU And this one, too: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DwkUW0mMkqE