DISCIPLINE AND RULES

- Rebecca Otowa

- Jan 9

- 4 min read

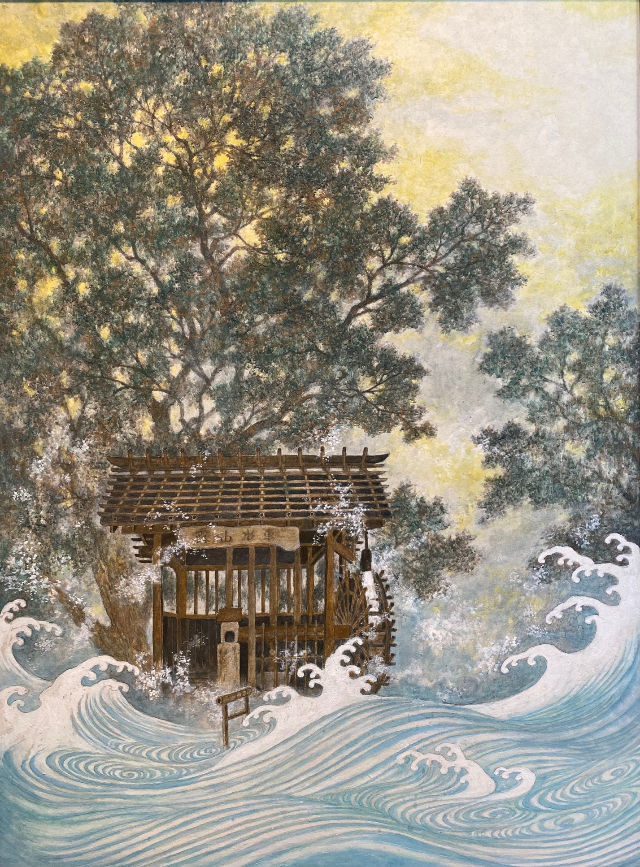

(The picture that appears here was painted by a local artist, my friend Hironaka Susumu.)

The word on everyone’s lips, with regard to Japan, it seems, is discipline. Influencers use it to rhapsodize about Japanese society. “Everyone is so disciplined here!” they sigh when they see, for example, little kids going to school by themselves on public transport or people lining up to get on one side of an escalator. They see the surface, but they don’t or can’t understand what’s behind it.

Japan is a country of rules, mostly unwritten and internalized in primary school or earlier. I remember my mother-in-law telling me that futon should be hung out in the sun for 60% of time with the inside out, and then turned so that 40% of the time the outside should get sunlight. The optimum time for hanging out futon is 10 am to 3 pm, which means that the futons should be turned over about 1 pm or so (after lunch, which should happen at 12 precisely). This was only one of the rules I was expected to follow as a young bride. Others were: food should be served on round trays and dirty dishes collected on rectangular trays; certain dishes were to be used only for certain foods in certain situations, etc., and of course, dishes should be replaced in their boxes and returned to the storehouse after air-drying.

Naturally I did not learn men’s rules, only woman’s rules in the house – but there are rules for things like how deeply to bow and what type of honorific to use with various people, how to hand over a name card, how and to whom to pour sake, etc. which men have to learn when they enter a company. My point is that this place has hundreds of rules that must be followed in this country in everyday life, and these rules are inculcated early.

Children get a good dose of rules at an early age. The traditional way of punishing a child here is to put them outside, and make it clear that for the duration of the punishment anyway, they are nakama-hazure (not part of the group). This is the ultimate worst fate of a Japanese, to be ousted from the group. (Ousting oneself is very rare). I am also reminded of one time at a sporting event in our neighborhood, at which a young boy fell and hurt himself, and we were responsible for contacting the family. The grandfather appeared, and without a word, smacked the child’s bloody head and then scolded, Meiwaku wo kaketa daro! (“You made trouble for someone!”) and in traditional weddings, the groom says, “We hope not to be a trouble to those who wish us well.” They have learned their lesson. Don’t make trouble, try to do everything yourself, and above all stay part of the group.

Everyone is a prisoner of the rules of their society, which are firmly tied to the language we learn to frame the world with when we are small. For example, in English, there must be a subject of every sentence; in Japanese, this is often omitted, especially in the case of people. “No need to begin with I, as it is clear you are the one talking” was advice given during a language lesson in Tokyo to David Sedaris (When You Are Engulfed in Flames, Little, Brown & Co. 2008, p. 276). Unlike English, Japanese is a listener’s language; it expects the listener in a conversation to fill in many things as a matter of course. English is much more direct, and many times I have wanted to exclaim, in frustration, “Why didn’t they tell me!” A case in point is the way students are expected to learn, especially traditional things. Instead of listening to a lecture or explanation, the student is expected to “watch and learn”. Even questions are not welcomed. The student starts at the bottom, washing dishes or preparing things upperclassmen will use, all the while absorbing things about the craft or discipline without being told about them in so many words. This is also how young wives, for centuries, learned how things were done in the husband’s household – in most cases, this is how the mother-in-law also learned them. The system is breaking down now, because young wives have their own homes instead of being taken in to a husband’s home when married; they probably learn things about keeping house from their own mothers, or perhaps don’t learn them at all. I don’t know; I only know how I was taught. Expecting an explanation, I was often scolded for not knowing something which I should have simply absorbed. My mother-in-law expected me to “just know” it, having observed her. Because I spoke Japanese, they thought I knew the whole culture as well, which if course was impossible for me.

This sort of conundrum is happening everywhere people try to enter another culture to any degree of depth, rather than simply learning words. Needless to say, I often feel wrong, sometimes actually crazy, because I can’t fit in with what the people around me want, which has little to do with what words they use. Knowing the language is only the first step, like the small waves which go up onto the beach; the ocean, of which the waves are a part, is always out there to be dealt with. Yet you have to start somewhere, and language is a keyhole to an entire culture.

This may be why “influencers” don’t probe too deeply in matters of discipline or other difficult and nuanced parts of the culture. After all, they are just trying to make a buck. Nothing but the simplest interpretation will do that on social media. What does that say about people who gush in the comments that the “love” Japan because of this, and hope that other countries will follow suit?

Japanese people are disciplined. There is no doubt about that. The real question is, what was done to these people (human beings just like you and me, whether they admit it or not) when they were being indoctrinated into their culture that caused them to be that way? And why do other cultures approach this problem differently, thus producing other results? This seems to need a discussion of shame vs. guilt, which I can’t deal with here. Maybe later.

Comments