HOUSE OR HUMANS?

- Rebecca Otowa

- May 6, 2020

- 4 min read

I haven’t moved house in almost 40 years. When people say “I just moved from City A to City B because of my job” or “I decided I would be happier in City C, so I moved there”, I think, “Where did they get the money to move?” Because we don’t have anything like that amount of money. We’re not poor, but moving to another place is beyond our budget.

The answer to my question, of course, is that they sold their previous house, and used the money they got from that sale to move. However, I can’t sell my house, therefore I can’t move.

Why can’t we, my husband and I, sell our house? We probably could sell it if we were determined to find a buyer. It probably isn’t worth much, relatively isolated as it is, far from railway lines and freeways. Still, it’s big, roomy, and solid; it has a good atmosphere, good feng shui, and is on the edge of the village, not hemmed in by other houses. The right person or group might jump at it.

But we wouldn’t sell the house, even if a buyer turned up on the doorstep tomorrow. This is because the house, and the surrounding land, have been passed on for twenty generations. Not necessarily from father to son – there are definitely a few doglegs in the succession – but it’s enough of a straight shot that we can’t sell it out of the family.

The tradition in Japan used to be for the eldest son to inherit the house. The parents gave a sum of money to the bride’s family and they were then responsible for wedding expenses. A second son might marry a girl from a family without sons and take their family name. Similar financial conditions would apply; certainly great care was taken to ensure that no large financial liability was shouldered by either family.

If a couple had a big house but no children, various negotiations would be conducted among the relatives to ensure that a child would be adopted into that family to ensure that someone would inherit the house. This happened to my mother-in-law, who was actually born next door. Her husband, the second son from somewhere else, married her and took her name, becoming the head of the household in the generation previous to ours.

It’s easy to figure out that for traditional Japanese people, the fate of the house was given precedence over the feelings of the living human beings who occupied it. Imagine a child of 6 or 7 suddenly removed from its biological parents and sent to someone it might not know at all – “You are part of this family now” – sadness, incomprehension, perhaps emotional or psychological problems later in life might ensue. None of that mattered, if it meant the house would be carried on to another generation. The house was more important than the humans.

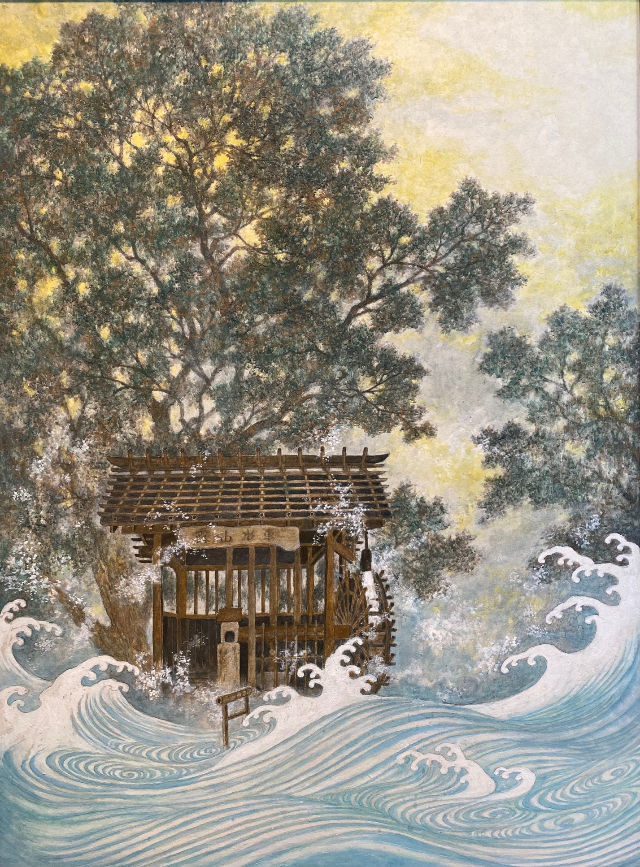

Why? Was the house valuable as property? Was it a source of security? Clearly so, but another reason for the house’s importance was because it was the only remaining earthly domicile of the ancestors. Members of previous generations were still part of the family, even though deceased – they helped to anchor the living family members in the place where they belonged. Continuity of place is a feature of most old cultures in the world, and apparently over 90% of houses in our area have been carried down from the past in this way.

People in traditional agricultural communities mostly stay put. Once in a while a younger son might have had a wanderlust to travel elsewhere, working for his passage on an oceangoing trade ship or joining the army; the family might have had a tradition of educating sons to be doctors, teachers, or lawyers, who might be a little more mobile than farmers were. Still, generally, the continuity held.

But in the past hundred years or so, these little countryside domains have broken down. Not only younger sons, but elder ones too, have much more curiosity about the great world beyond the hills. Education has played a large part in this, as well as mass media, movies, radio, and television. How are you going to keep them down on the farm? It may offer security and continuity, but these things pale (especially for young people) in comparison to risk, adventure, and that greatest of modern human concepts, individual freedom.

The quandary of who takes over the family plot and place has become moot. Elderly parents no longer really expect the eldest son and his family to move in with them. Perhaps later, when he retires, he might find the idea of country life more attractive, especially if he was raised there. By that time, however, his own son won’t have any particular connection with the place, so the chain will be broken in the following generation anyway.

My son, the 20th generation of our family, has recently moved back in with us. His children are still primary school age, and one of the main reasons they decided to live with us is so that his own son will feel a connection with the place and maybe take over in his turn. The pull of the ancestral house and land is quite strong, especially when it’s a good generous house as ours is.

I’ve always had a real affinity for the house, the way it feels. My son and his wife are planning a lot of changes, and a fresh new breeze is blowing through some of its dark corners. The house is taking a deep breath and shaking off the confines of a hundred years of inertia (the last big remodeling was in 1847). It’s surprised, but I don’t think it’s displeased. Best of all, it feels safe for another generation, because my son and his family appreciate its age, its benevolence, and the way it has sheltered our family down the years.

This house isn’t a museum; every generation makes changes to increase its comfort and convenience, and some things are kept (the oldest object in our house is a wooden box dating from 1547). That is as it should be. Earlier generations might not even recognize the place as it is now. The spot where the house has stood, steeped in our family’s vibrations, that calls to certain members of the family to come, to live, to keep it up – that is the important thing. We are indeed lucky to have one place on the globe that is truly ours. And it’s my honor to be part of it.

Incredible read. We love these cultural observations. Such a narrow and fascinating topic. Makes me realize that there are millions of interesting stories all over Japan about the fate of the homes.

Hello Catherine,

I live in the village so I do not have a well for water, if that is your question.

The house is 104 years old and I am the only one that has done any changes to it.

The kitchen was large when we moved in in1971but one wall had 4 doors on one wall, a door on the other, and a window on most of the third wall, so my Dad and I extended the fourth wall out about 4 feet and put a window in for over the sink ( not a good idea to put the sink out there moved it back sometime later into the main space ). Also added a greenhouse for the…

I had moved a lot before we bought our house. I doubt it will be something that will last as long as yours.

Do you still have a well?

This is very interesting.I just finished the At Home in Japan book. It has shown me things that I did not know about Japan. I have a Japanese antique shop and many different tansu in our house.My first wife ( passed away 4 years ago ) was Japanese -American,born in the camps during the war, my present wife is from a little place called Moriyama in Isahaya ,Nagasaki. Her mom lives in a home that she built about 42 years ago.But it is very traditional.

Her mom was a farmer but had a stroke last year and can not do it anymore.Her sister lives with her but I`m afraid that when she passes ,the the house will be sold.I wou…

As one who has moved so much and never stayed in one place more than a dozen years or so, I envy your "grounding" in time and place.