LEGACY

- Rebecca Otowa

- Apr 1, 2020

- 4 min read

Like many of you, I am spending a lot of time at home these days. Though there are those that deny and ignore because the numbers of cases and hospitalizations in Japan are so far relatively favorable, I feel it’s my duty to act as though I live in a “hot spot” and keep a low profile socially. And like I imagine many of you are as well, I am saying daily, fervently and sincerely, thank goodness for the internet!

There are other things I can say thank goodness for. My home is large, with land around it, so there is plenty to do. In addition, I am preparing to divide my house into two: the younger generation (my son and his family) will soon take over the main house, while the older one (my husband and me) begins residence in a smaller set of rooms on the sidelines. Lots of work to occupy me there.

Confined to a certain space, I look more closely at things around me. I’m a “crafty” person who is never so happy as when I have some kind of project in the works, be it a painting, a piece of writing, or something I’m making by sewing, knitting, beadwork, stained glass, or (basic) woodworking. Soon I’ll be gardening as well, growing summer veggies for the family.

What I have begun to notice about these things around me is that everything I deal with, everything I touch, has been made by someone else, unless it is growing outside in nature. Maybe I can put things together in a new configuration, but who made the component parts?

Take my latest love, stained glass. Sure, I know how to cut, grind, and put together the pieces, and I usually make my own designs instead of working from a pattern or kit, but can I make the glass itself? Could I fashion the tools I use – cutters, grinders, soldering irons? Some stranger did all that. I am sitting on top of a giant pyramid of human ingenuity – and so is everyone else in the developed world.

I used to teach a university English seminar called “Thinking about Human Life”. I would give each student a ball point pen with a transparent barrel, which are a dime a dozen (actually about a dollar each)and ubiquitous everywhere you look. I would have them watch what happens when they push the button at one end so that the point comes out the other. It’s actually quite an ingenious little mechanism, powered by the thumb alone. Somebody thought of that; it’s one of the small miracles of our modern age that nobody bothers to notice. I also asked my students to count the various parts that made up the pen, and to envision someone designing and then manufacturing each one; then a factory in which all the parts are combined to make a pen; then bundling pens in boxes of 100 or whatever and transporting them to shops where people like us can buy them.

It’s the same with almost anything we encounter or possess these days. We usually don’t make the tables and chairs where we sit, the dishes we eat from – the very food we eat comes from the hands of strangers over a long chain of effort that stretches from them to us. Sure, I am handy, I can make things, but not from scratch.

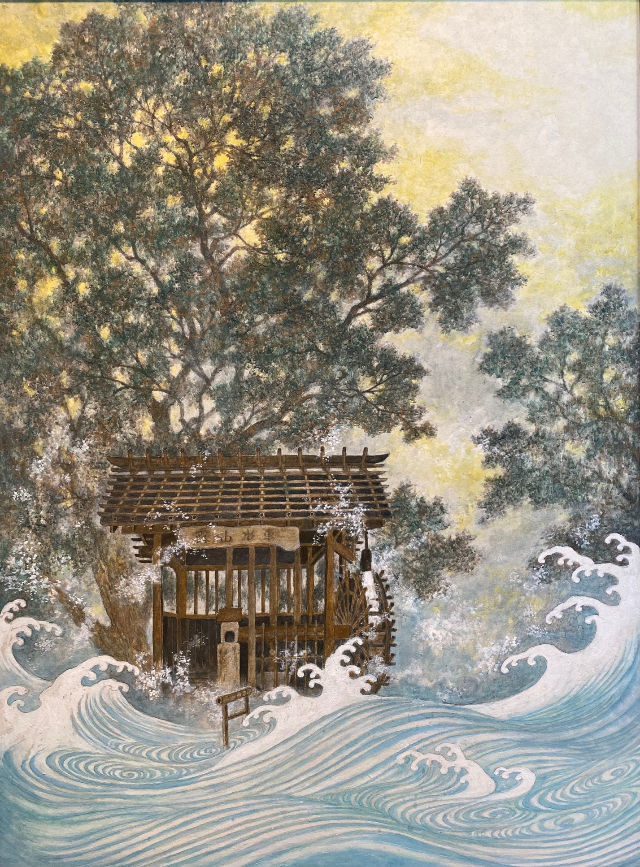

My farmer’s life brings me a bit closer to the place where scratch things are made. Small farmers are experts at improvising useful things out of what is lying around. The simpler these things are, the more different uses they have. A stick can be used to support or to destroy; to join or to separate; to lift up or to press down. A simple tool, such as a small weeding scythe, can be used to cut string or dig a hole as well as pluck out weeds. I feel good using these simple tools because I feel closer to the people who make things from scratch. Around my home there are many objects made years ago by hand, often from the simplest materials: straw, wood, bamboo. It’s human ingenuity – the tool-using part of us – that looks at something and says, hey, I can change this a little and then use it to do something else.

When I lived in Europe, I had occasion to visit many different kinds of museums, and the ones I liked best showed how, before the industrial revolution, people figured out how to do things, sometimes insanely complicated things. How about making a ship of wood, cloth and rope that could sail from one continent to another? How about mapping the world with a painstakingly created handmade sextant or astrolabe? How about inventing ways to communicate by making marks on cloth, wood, clay or paper? How about figuring out how to keep food by fermenting it, how to change material, like wood, into charcoal so it burns better? At these museums, I used to whisper to my husband, “Somebody had to think how to do that!”

It’s human ingenuity that grabs me, every time. And in this enforced slow-down period given us by the coronavirus pandemic, we have time to feel all those centuries before us, all those people of flesh and blood, just like us, who saw problems and went about solving them, with little to aid them but trial and error and that incredible tool that we all keep in a globe of bone between our ears.

Our lives make use of the legacy of all those people. Now we have time to notice it and use our imaginations to trace the things we use back to their raw materials, and to feel the centuries of hard-earned human know-how that went into them. Anything! Anything that you see and hold and use every day, just take another look, another feel. Each item has a family line, a history that can be traced back and back. And if you ever have the amazing privilege to make something “from scratch”, don’t pass it up. There is nothing more satisfying.

When I lived in rural Tottori, while visiting a friend's old farmhouse, he took me inside the family kura. Everything it contained was from before the war. It amazed me that I was surrounded by things handmade, each brought into existence over many days or weeks. Indeed, a slowing of time.

I love this post Rebecca. Your approach reminds me of the Japanese word ‘Itadakimasu’, which I use before I start each meal, as you do no doubt. It shows gratitude towards everything and everyone involved in the production of the food on the table. We can extend this to all aspects of our lives and be in awe of the creation of the world around us. :-)