OUR BRAINS ARE BETTER

- Rebecca Otowa

- Jun 28, 2022

- 5 min read

Happy Solstice, everyone! We in the Northern Hemisphere are now at the top of the Ferris wheel of the y

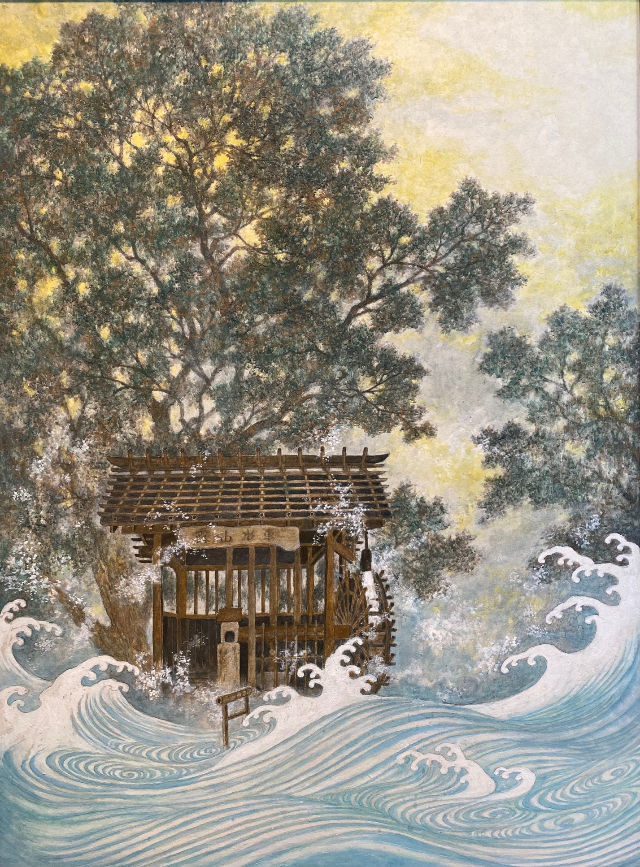

ear. Midsummer… everything is green, growing, and busting out all over. Please check out the new pictures here – the title, the self-portrait, and the bottom of the website.

This time I have chosen to write about a ubiquitous and would-be convenient aspect of our everyday lives – the sensor. Recently on social media, a friend recounted how, in a parking lot, he suddenly heard a mysterious voice say something like, “Unauthorized approach. Do not touch.” This turned out to be a sensor alarm for a car that he was passing. I expect that if he continued to approach the car, a loud alarm would sound, and he might have found himself in trouble.

Perhaps not, though. Car alarms are an irritating fact of life these days, and rather than investigate, people tend to jam their pillows over their heads (it often happens at night) and wait for the alarm to cease. Are these things as efficient in deterring crime as they advertise?

But imagine if it was your car. Either you would physically hear the alarm (unless you were asleep) or you have some kind of electronic device that tells you when the alarm has gone off. You would first have to recognize the alarm as yours, among all the other possible car alarms in the area. Then you would have to go to your car, check that things were all right, and turn off the alarm. You have been taught how to react by a sensor. The series of very complex actions that you have to take are all determined by the alarm going off, which may not have anything to do with an intruder anyhow. (This is eerily similar to what happens when your phone rings in your pocket or bag, I just realized.)

Or take another sensor that we are very familiar with – those of water faucets in public toilets. We have had to learn that in order to get the water to flow, we don’t turn the faucet handle as in days gone by, we swipe our hand (sometimes repeatedly) under the faucet to activate the sensor. If we are doing something more complicated, as when I used to brush my teeth in the public bathroom just before visiting the dentist, we may need to activate the sensor several times to get enough water. Why do these water faucet sensors exist? One imagines, to save water in case one of us forgets to turn the water off manually. Or as a prank? As Jerry Seinfeld says in one of his routines, “What is it that they think that we would do? Turn on the water and then run outside, laughing and pushing each other into the bushes?” Another possible reason is to avoid touching the possibly germ-ridden faucet handle – but after all, you are washing your hands anyway. It would be easy to wash the faucet handle at the same time as you wash your hands, and in fact I often used to do this as long as my hands were soapy.

Before sensors, we had those “spring-loaded, pain-in-the-ass Alcatraz-style faucets” (Seinfeld) that I’m sure many of us remember from our school days. The water couldn’t run while you soaped your hands, because one hand always had to be on the faucet, keeping the water running. They may have saved water, but they certainly didn’t encourage good hygiene.

Before this, in many places there was a water container with a small metal bar attached to a spring, which you would push to start water flowing. The bar would gradually return to its original position, shutting off the water flow. This required filling up the container every so often; but it was entirely mechanical, and no electricity was required to run it. (These are still on sale; you can find them on the Internet.) I remember these in my home when I was first married, and I’m sure similar devices existed in the West too.

But my point is not that sensors are ubiquitous (they are, and I’m sure the sensor companies are making money hand over fist in this day and age), but that sensors could not exist without our brains. Of course, they would not exist if someone didn’t think of and design them, but that is not what I mean. For most sensors, the human brain is essential for proper deployment. We don’t even notice it any more, but we have been taught to activate sensors to preform many tasks in everyday life. Without adapting to the needs of the sensors (for example, moving our hands under the faucet) they would be useless.

And I don’t intend to begin to address the issue of all the different beeps and bleeps, emitted from electrical devices for various messages, that we are expected to learn to differentiate in our homes. Perhaps these don’t qualify as sensors, or perhaps they will be the subject of a future blog.

How much more or less of our brain is required to set off a sensor than to simply turn the water on and then off as with a regular faucet? And we must also consider that, more often than mechanical faucets, sensors regularly malfunction. We have all had the experience of swiping our hand repeatedly under the faucet, only to discover (sometimes after many tedious seconds) that the sensor isn’t working, so we have to move to the next sink and repeat the process. And don’t even get me started on the sensors that supposedly flush the toilet. Fortunately, a “Plan B” button is usually provided. Don’t they trust the sensors? Apparently not. Then why install them in the first place? Why not just flush normally or, even better, use the money to devise a foot-pedal style spring flushing mechanism?

Quite often, too, the sensor seems useful and convenient, but actually does no good at all. One example is the distance-sensing mechanism in my (3-year-old) car. When my fender gets too close to another object, a loud beeping is set off. It’s usually far too late to avoid whatever the object is, or else my driving is sufficiently good to avoid the object even without the sensor; but it can’t be turned off, I think all new cars have to be provided with this by law, so I have to drive all the time wondering when a loud, irritating beeping noise will cause me to startle and jump, in theory making it even more likely for me to have an accident while recovering from the beep. No amount of teaching or learning on my part will save me from this sensor. And as far as I can tell, it’s unpredictable. What a nightmare. Reminds me of another useless invention from around the 1970s: the seatbelt wired to the ignition so you couldn’t turn on the car without first fastening your seatbelt. I can’t tell you how many headaches that provoked. Whether it malfunctioned or not, and it often did.

We are already quite capable of doing the physical things necessary in our lives, without having to learn a whole new series of thoughts and actions to navigate the sensors as well. Bring back the ordinary eye-hand coordination of the time when the only sensor we encountered was the automatic door into the supermarket. Especially when leaving the supermarket with hands full, that is an example of a useful sensor. (I remember how magical this seemed to me as a child.) Our brains will always be better than sensors.

Am I just a cantankerous old person? After all, I had to learn to twist the faucet as a child. But the ways devices force us to adapt to them are getting more insidious, I feel. It’s just an example of the increasingly complex and electricity-reliant the human race has become. You know, these sensors will all fall silent when the electricity is gone.

When the electricity is gone someday.....other annoying things we can only imagine will replace all of the electrical annoyances.