PIONEERS

- Rebecca Otowa

- Apr 6, 2022

- 6 min read

Updated: Jun 29, 2022

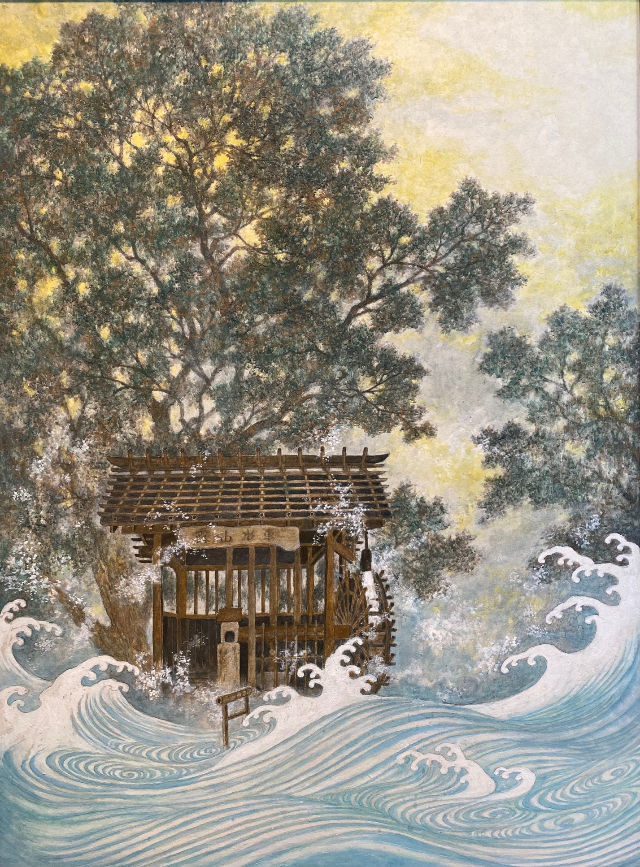

Photo courtesy of Ulena Switucha, circa 2009

(Happy Spring, everyone! Please check out the new photos on the website. I have now been writing this blog for two years, trying to make every blog about the same length, 1000 words or thereabouts; but lately, no matter how much I cut, I can’t say what I want to say within these limitations. So I’ve decided to write as much as I need to – sometimes the blog post will be longer, sometimes shorter. This is one of the longer ones.)

This month I received an invitation to speak at the Kominka Summit, a weekend gathering of people interested in or inhabiting old Japanese houses, mostly in the countryside. Kominka means “old family or tribal house”, and these commodious structures, ranging anywhere from 100 to 400 years old, have been cared for through succeeding generations by family members. I myself live in one of these, my husband being the 19th generation of the family. However, this system of family succession doesn’t match the modern lifestyle, because especially since the war, younger people tend to move to the city where there are more possibilities and jobs, and don’t stay in the countryside.

Family succession of this kind has continued because people thought it necessary to preserve the family seat (with the ancestral tablets, etc.) in a package with house and land, and to give it to the eldest son, providing for other family members in other ways, because if you keep splitting up property, eventually it becomes too small to be viable. But this system, alive and well for centuries, which put the welfare of the family seat first and the happiness or fulfilment of the living inhabitants second, is breaking down. In only a couple of generations, the livelihood and lifestyle desires of the living descendants have gradually supplanted the importance of family continuity in the national psyche. It is generally impossible for the physical house to follow the next generation to the city, which means that the Japanese countryside is emptying, and more modern houses, which are emphatically NOT built to last for generations. are proliferating.

As a result, these huge and usually very well-built structures are going begging all over the country. “Empty house banks” both public and private have sprung up as real estate people realize the value of these structures to certain people, who renovate them and often use them for businesses such as cafes and pensions. The Kominka Summit is one manifestation of the present burgeoning interest.

I’m going to participate in a panel discussion about getting along with the people that live in the village or neighborhood which the old house one has decided to buy and transform is part of. After all, these structures were meant to be in a certain place, part of a certain community, and to shelter a certain kind of people. In preparation for this, I have been thinking deeply about the people around me in my neighborhood. Lately I have felt a shift in my own thinking. Maybe the villagers would not agree, but after all these years, I feel like a villager myself, and I find I sometimes share their attitudes.

As young people have greater opportunities to travel and experience other cultures, some of them understandably feel cramped by the old ways and decide to leave their country homes permanently. Others look around them and realize that if they are going to have a family and a modern lifestyle, they need more money, so they go to more populated areas in search of job opportunities. Those who are left are usually the elderly and those who care for them, and now there is a new group, younger people who want a more slow-paced life, closer to Nature, than the hectic cities can provide. Both the young people who leave for an unknown fate and those who come to the countryside, often with no family connections, probably consider themselves pioneers, adventurers. Any new place is an adventure, when you think about it.

People who have decided not to leave take over the family business, or they care for infirm or elderly relatives. Some of them branch out into new things like organic cash crops or small tourism-related ventures. Most of them would say they “can’t” leave. These people are often derided by their more adventurous fellows, but staying in such a community has its own challenges. “They also serve who only stand and wait” could be a truism for these people, without whom the countryside would be empty indeed. There are also individual psychological considerations. My own dad had such itchy feet that he took his whole family from the USA to Australia in 1968, when I was 12, and that’s where my life really began, as I started to study Japanese in high school. I myself left for Japan in 1978, never to return to my parents’ home. Instead, I found myself in this place among people who have known each other since childhood. I chose this, and I’m glad now, although I sympathize with all the people who never thought they had a choice.

What I’ve been thinking about, as I am now on the very threshold of old age myself, is how elderly people are seen in the new youth-oriented culture. We (provisionally, I’ll use this pronoun) are accused of clinging to the old ways, of not being adventurous. We are liabilities, bothersome financial drains on families and governments. Meanwhile medical science finds ever more convoluted ways of increasing human life span and denying the cold hard biological facts of the aging body.

But in our way, we old people are pioneers too. We are also trying to live in a way that, up to a couple of generations ago, has never been known in all the past centuries of humanity. It was uncommon for human beings to live more than 50 or 60 years in the old days; diseases and accidents carried people off as a matter of course. Now we don’t have a say, we are dragged willy-nilly into older and older age through medical breakthroughs. The often painful and humiliating ways the body changes may be felt as personal failures by elderly people, even though it isn’t our fault; our life span has been increased while we are still living with the same type of body our ancestors had, parts of which simply fail after a certain number of years. How to deal with a body that suddenly doesn’t want to do what it always did? The various slowdowns, leaks, and breakdowns are just as frustrating as handling an old car. Doctors, who may be decades younger than their patients, are no help, labelling conditions as “just getting older”. Wait until it’s your turn, I always think. Elderly people have to deal with this kind of thing every moment of their waking lives, and for this, I would like to call them pioneers. They are navigating a country young people know nothing about.

For the people who are still living in rural districts (actually the world over) life is not exactly a bowl of cherries. They must deal with their physical problems without specialist doctors nearby, and also feel useless or denigrated by the world they see on TV or on the internet. Their own world is disappearing out from under them, and in its place a world they don’t understand has come to be. We are only the second or third generation, I said recently to my husband, in which things we don’t understand at all, especially digital devices, are in everyday use. Even cars used to be taken apart and then reassembled! By teenagers!

Perhaps everyone on the planet is a pioneer in his own life. We are all struggling to stay on top of an increasingly incomprehensible world. It isn’t hard to imagine that some people might feel like they’ve had enough. They long to live in a world they can understand and not be pushed into changing in ways they don’t want and feel incapable of. Being able to jump when circumstances say “jump”, adaptability, is a skill highly prized in modern life. Staying still, being quiet, enduring, holding on, are less prized.

Let’s be gentle with those around us, whatever choices they have made. They may be pioneers, forging new paths in this adventure called human life.

Dear Rebecca,

Every time you say to look at the pictures, but you do not say where there are to be found on your website. I'm looking, but I'm not finding ! I've left the same question below one of your winter posts. Can you please answer ?

I love reading your thoughts, as always.

Emma