RAIN, CLASS AND OTHER EPHEMERAL THINGS

- Rebecca Otowa

- May 20, 2022

- 5 min read

While assisting two old ladies from the local work service to weed the garden on a recent cool and cloudy day, one of them looked up and said, “It’s raining” (ame). I myself had felt only one tiny drop on my hand.

Scrolling through my YouTube feed yesterday, I came across Tan France of Queer Eye, an Indian by birth, talking about how he felt pressured to do “skin lightening” treatments in his youth.

What do these two things have in common? Read on; I’m going to try to connect them.

Let’s consider the second one first. It seems to be universal in societies around the world that lighter skin is “better” than darker skin, if you have the means to change it. All kinds of makeup, bleach, tinting, cover-up clothing, etc. are used to achieve this. In Japan, farmwives cover themselves almost completely when going out to the fields, because they don’t want to have darker skin due to suntan. They wear long sleeves and long pants, hats, towels, masks, gloves, etc. Only a very small slit for their eyes shows that there is a live human being in there. And it is well known that high-class traditional makeup in Japan is chalk-white. I myself had to be painted white on hands, nape, and face with a paintbrush when I got married in traditional dress! My “ordinary” European whiteness wasn’t white enough, it seemed.

Light in general seems “better” than dark. For years rich people in Europe and America showed their “class” by insisting on eating white bread with, incidentally, most of the nutrients (such as the germ of wheat) removed, and the same is true of many Asian higher-class people, rejecting brown rice in favor of white. These food prejudices have filtered down to ordinary people; few people I know in Japan eat brown rice by choice, it has rather been common practice for years to “polish” rice to get rid of the brown color, wherein, sadly, reside most of the nutrients. You can even buy home rice polishing machines, with varying levels of white in the resulting white rice to choose from.

Why would people volunteer to eat nutritionally inferior food simply because its color signals some kind of superiority? I guess in the old days white bread or white rice was more expensive, thus if you could afford it, you were higher class than others. It also signified wilful waste, which has long been a sign of wealth, ridiculous though the notion is. Consider Louis XIV and Marie Antoinette having food fights in front of the starving peasantry.

Sadly, food is only one of the things human beings have used through the ages to feel superior to other human beings. There are a couple of other interesting examples in the Western world. One is language. In English, anyway, grammar and spelling, quite aside from accent or dialect, were artificially invented so that people could tell by your words what class you were. One laughable example from (I’m pretty sure) 19th-century standardization of spelling is the word “island”. There’s really no reason why the “s” should be there, it just looked classier to those who were making these kinds of decisions. The Latin insula has the n and s reversed, but the s is there, so it is likely that the present headachy spelling harks back to a culture which revered Latin (many private schools listed Latin on their prospectus for this very reason). Unnecessary things, even to silent letters in words, have long been a hallmark of higher-class life. Similarly, table manners. All the strange little rules that used to make dining out in polite company such a hassle originally evolved to make some people feel superior over others. Don’t put your knife in your mouth! The salad fork should be used for salad! Don’t tip your soup bowl toward you, it must be tipped away from you! But why? No particular reason. These actions became like passwords to allow “cultured” people to recognize each other. And many people adopted these manners in order to seem more cultured themselves. I suspect this was a primary concern of “nouveau riche” or self-made people, which suddenly found themselves richer in money than in “breeding” and strove to enter polite society. Hence the obsession with “etiquette”.

So where does rain come into it? This is a connection that I have made myself; though it may not be verified in sociology, it seems logical. I have long noticed that Japanese people treat rain as some kind of monster. From my years in Australia, I have become quite hardy about rain. In my experience, we don’t immediately say “It’s raining” when we have felt a couple of tiny drops. We say “It’s spitting” or “It’s sprinkling” or “It’s drizzling”. “Rain” is a really big deal. It’s torrential, it can cause floods. As a student in Kyoto, I used to laugh at people who seemed so scared of a few little drops of water. They always carried umbrellas and put them up at the first little “spit”. Many of the Aussies I knew didn’t even own an umbrella!

There seem to be two reasons why Japanese people are more sensitive to rain. One is practical. This is a culture where everyone airs their bedding at every opportunity, and most people still hang out their wash. Of course, you wouldn’t want a cotton batting futon to get soaked with rain, and some people think clothes that get rained on become stained (this probably made more sense when rain was actually dirty with smoke from wood fires, etc.) Naturally you would scurry outside at the first hint of rain to gather in your futons and washing.

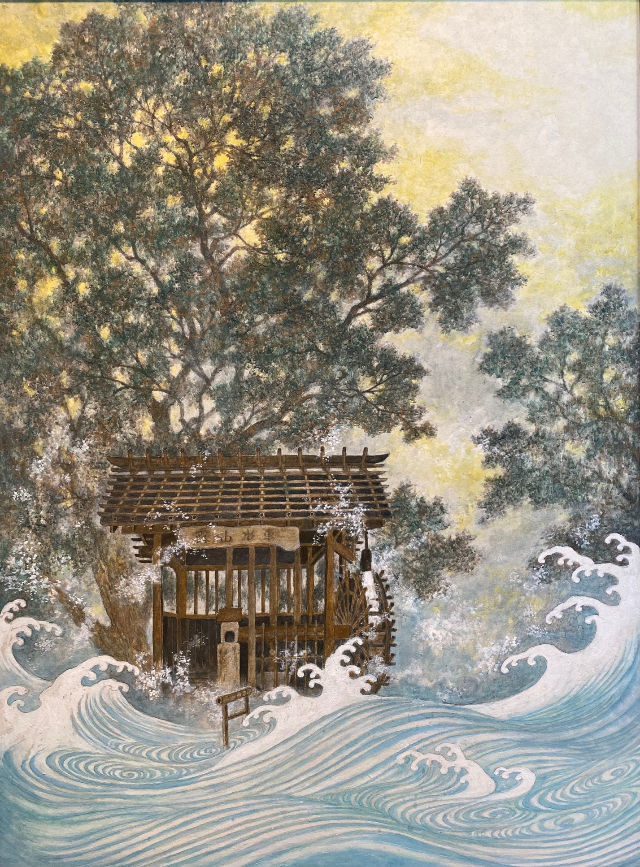

But I believe there is something else. Even if you have no futons to bring in, there is a distinct class meaning to being sensitive to rain. Rain ruins silk, and silk was the fabric of choice for high-class kimonos – it still is. It seems to me that if you wanted to appear high class, you would call attention to the fact that it had started raining, just as a silken-clad noble beauty would. Ordinary people in Japan, I’m pretty sure, paid just as little attention to rain as ordinary people did the world over. After all, unless it is really pouring, it doesn’t affect your ability to work outside. All it means is that you will get wet. That probably happened several times a day to farmers working in ankle-deep pools in rice fields or washing wooden boxes or baskets in a local stream. They didn’t have the time or energy to fiddle with handmade oiled bamboo umbrellas. They might wear a straw cape (mino) but that was about it.

Does fashion still win out over usage? Is it still considered laudable to feel superior to your fellow person and to indicate this by various subtle ways of dress, words, or action? Well, I think it’s less important to the ordinary person than it used to be, when accent or manners automatically disbarred them from many essential things. But we still have these echoes, and of course, we have invented many other cruel and sad ways of feeling ourselves better than each other, thus more secure, in human society.

I always thought it was somewhat incongruous that Japanese women used to dye their teeth black -- but I guess that was mostly about hiding defects -- and making their faces look even whiter, with the contrast.

Nicely tied together, Rebecca. Clearly written--as always. I imagine that you have thoughts on Japanese culture that have never crossed the minds of some of the students who are likely to attend our November event. I think that the types of observations you make in this piece and others will be very interesting to them.