SUDDENLY I REALIZED…

- Rebecca Otowa

- Jun 21, 2024

- 5 min read

Updated: Jun 21, 2024

June 20, 2024 (Solstice)

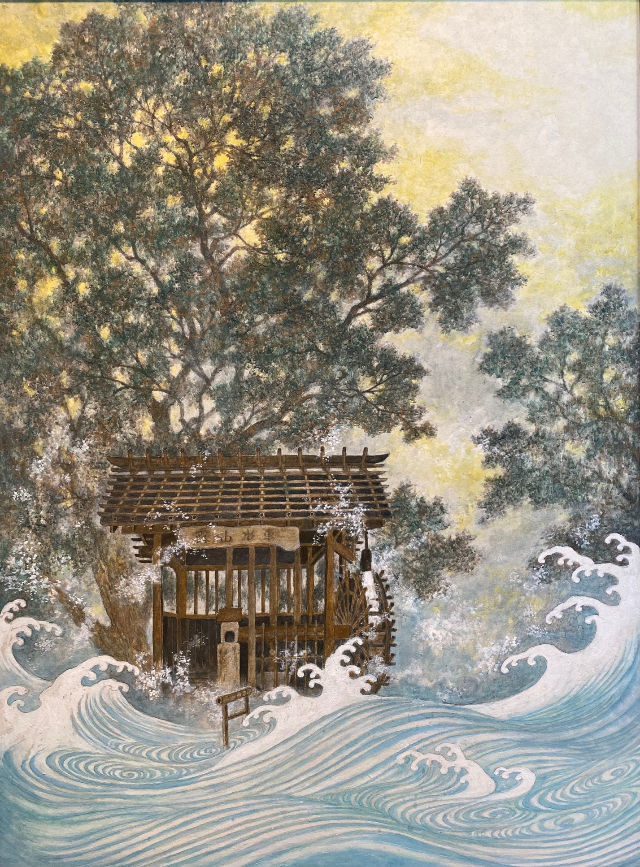

(This is a summer solstice post, when the day is the longest of all the year. At present I am reading “The World According to Colour” by James Fox, and I am now learning about the cultural associations of Yellow / Sun / Gold. From now on our lives will be lived on the descending side of the great Ferris wheel of the seasons; but because the Earth is slow, for awhile longer we will feel the effect of the Sun’s heat and light as the most intense of the year. Best wishes to all for the Summer season. Please check out the new seasonal pictures on this website.)

When I was a child we often watched a TV series called “Sea Hunt” starring Llyod Bridges. Since he was usually underwater alone, his conversations took the form of narration, and his favorite phrase was “Suddenly I realized…” as in “Suddenly I realized that my air was running out”. This phrase was so prevalent that our family took to calling the show and its star “Mr. Realize”.

But it’s true. It has taken me almost half a century to “suddenly realize” one of the most important underpinnings of Japanese culture. I was discussing overtourism with my Japanese daughter-in-law, as it is in the news now, and I was wondering why they don’t just penalize wrongdoers with fines etc. The word would get around among tourists. She said that that wasn’t the Japanese way – socially and culturally, they put out hints or guidelines, not rules or laws, and wait for people to understand them collectively.

This seems overly passive to those of us brought up in western cultures, where rules are Rules and you can expect a no-nonsense rap on the wrist if you don’t obey. Why do these rules exist? In order to bring individual wrongdoers into line with society. I think it comes from the idea of a punitive deity who will judge us as fit for Heaven or Hell. We instill guilt (conscience), which is an internal emotion in which the wrongdoer compares his individual actions with those promulgated by a religious or social ideal. We say of psychologically damaged psychopaths or sociopaths that they “have no conscience”. This is frightening to us, because an individual conscience, to us, is what “puts the brakes on” potential wrongdoing, ie. actions that are not conducive to society’s smooth running. We are trained to judge actions by individuals as acceptable or not, and we need to trust that others have the same judgment going on in their own individual minds. We learn how to deal with other individuals’ ideas of what “acceptable” is, either to accept this or to reject it in favor of our own judgment. We learn to deal, to decide what is our own province or problem and what isn’t, to set boundaries, and we become “well-adjusted” – or we don’t, and our lives become a miserable circle of judging others and ourselves.

In this sense, we non-Japanese often experience this culture as passive, because individual action and evaluation take a back seat to group concensus. Passivity itself, presented as an absence of the more desirable active mode, is seen as negative and undesirable in the West. But the group nature of Japanese society means that passivity has a positive connotation. To be like this is to be tuned into the feelings of the group, which is the way things work here. Individuals (and they are all individuals, as all human beings are; they are simply conditioned to behave as a group) are expected to “take the hint” and fall into line with the group. Either that or they brave the world of individuality as represented by Western culture – most, I expect, take little forays into it and then retreat, with relief, into the solidarity provided by the group.

One problem of interactions between Japanese society and (for example) tourists in Japan these days is that the “hints” provided are often not understandable except by other Japanese. An excellent example is the tune “Auld Lang Syne” which is originally a nostalgic look back, a drinking song, which has come to express the feeling we get just before the New Year starts. In Japanese (“Hotaru no Hikari”) it is a graduation song in which students recall the hardships of a studious life. In other words, in Japanese the tune represents endings (the end of student life), and is used as a hint in stores, offices, libraries, etc. to signal closing time. It is only to be expected that foreign tourists would not recognize the meaning of the tune in this context, thus ignoring the “hint” that the place is about to close, causing trouble for employees trying to herd them out (as reported in news articles recently). The “taking of the hint” provided by this tune probably arose as mysteriously as, in Western culture, this tune came to be associated with New Year. It would take some digging to trace these associations. At some point someone, or some committee, decided in Japan that this tune, when played over a PA system, would connote imminent closing of a facility; everyone eventually “took the hint” (who knows how long it took?) and now it is ubiquitous. I can’t imagine that it was the result of some individual “activism”.

For a person raised to believe that the individual mind is the core of human activity, it can be excruciating trying to fit into a group. Conversely, for a person raised to believe that the group, and membership in it, is the pinnacle of social relations, to be seen as an individual and expected to behave that way must feel quite lonely. I once read a passage about primitive peoples. Was it more frightening for a caveman who was used to thick forest to suddenly come upon an open plain, or for a plainsman to explore the thick forest? This analogy is interesting when applied to this dichotomy between Western and Japanese (Asian?) culture. I myself would equate the forest with the group (scarily claustrophobic) and the plains with the individual (scarily loose and open).

This is, I know, just a generalization. But this realization, that these two modes are simply different ways human beings have evolved to deal with social settings, not that one is RIGHT and the other WRONG, I suspect will usher in a new phase of understanding of people closest to me.

Western people have a saying, “When in Rome, do as the Romans do”. Japanese have a similar saying, Go ni yukeba go ni shitagae. It can be very hard to do this without losing my own identity, what makes me me. Each culture demands no less than total allegiance, at least in this phase of human evolution. But it is never total, either for the person doing it, or for the people around them. (This is a huge subject and one which I may treat in another blog.) It is up to each of us to decide how much we can give up, when we make the move to live out our lives in another culture, and this decision changes often. It is possible to go along with another culture’s demands for years, and then suddenly our own identity rebels, it needs to be heard. This would be equally true for forest people who elect to live on the plains, and for plains people who venture into the forest.

Someone once said to me that the type of foreigners who are most content in Japan are those who are used to being alone, and don't suffer from loneliness. The longer I live here, the truer this seems.