TWO KINDS OF FOLK SONGS

- Rebecca Otowa

- Apr 8, 2024

- 5 min read

One of the few things I like about travel (as I get older, I increasingly don’t cotton to the uncomfortable aspects of it) is the opportunity to contact aspects of culture which don’t necessarily make it into tour guides. My husband and I have had a chance to visit several places in Japan over the past few years. Every place has its own history and culture which are sources of pride to the inhabitants, and there are various Societies for the preservation of tangible and intangible cultural manifestations.

One that I particularly like is music; I have been a big fan of ethnic music of all kinds for years. Recently we went to Okinawa for a few days, and that reminded me that we had gone to the Gokayama area of Toyama Prefecture a couple of years before (I wrote about this in Blog 29, “Another Kind of Life”). In both places we bought CDs of representative folk music, and recently I’ve been thinking of the characteristics of both kinds of folk music and how different they are, as they are from very different environments within Japan. I’d like to introduce these two types in this blog. I encourage you to look up some of the songs from these regions and listen to the differences yourself.

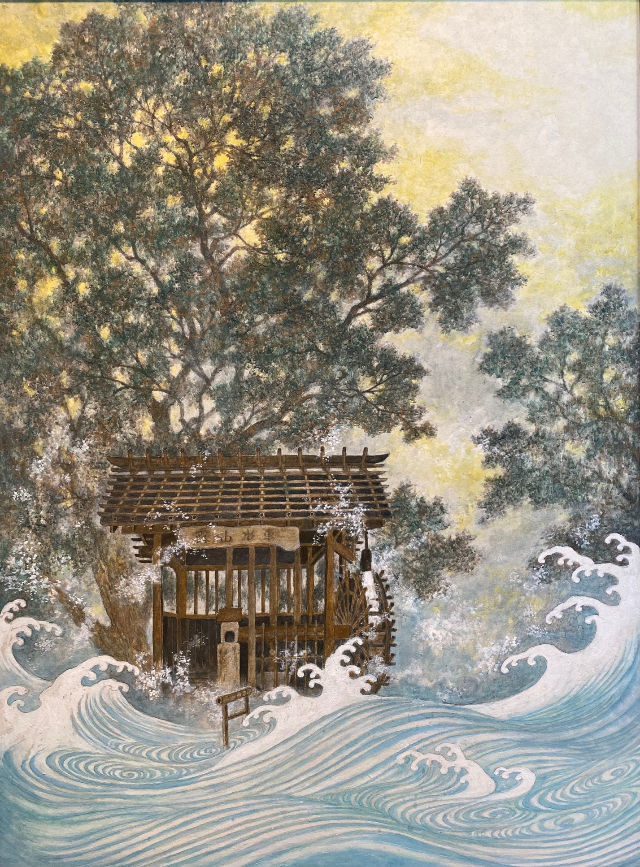

The Gokayama (5 Mountains or 5 Valleys) area of Toyama is extremely old. This is an isolated region of rushing rivers, steep valleys and deep snow in winter. It traces its history back to the Jomon Period (prehistoric, approx. 14,000 – 300 B.C.) At the end of the Heian Period, in the 12th century during the wars between the Minamoto and Heike clans, it was said that many of the defeated warriors of the Heike settled in this region. Due to the valleys being unsuitable for rice production, the major food was mugi (barley or wheat). Manufacture of silk and washi paper provided necessary cash. Also, a component of gunpowder, nitre or saltpeter, was secretly made under the floors of the traditional A-frame houses for various military projects, notably the Warring States period in the late 1500s, when guns first were used in combat, and government defense movements against foreign incursions after Commodore Perry’s forcible opening of the country in the 1850s. After the Warring States period, in the relatively peaceful but heavily restricted Edo period, the area was used as a penal colony instead of the more traditional remote islands, which were not available – samurai were banished here, and underwent the harrowing journey across the roaring rivers by kago-watashi (basket crossing) – an exiled person was placed in a basket and this was hauled over the river on a rope; it was said that this method discouraged the exiles from escaping, as bridges over the rivers were prohibited from being built.

When I visited the Gokayama villages I was struck by their smallness (the valleys are extremely steep and narrow), the dark and uninviting A-frame houses, and the brooding peaks all around. I imagined myself as a young bride coming over the pass to live in one of these houses, in the stink of decomposing nitre under the floor, probably hungry much of the time, hounded by alien relatives and mothers-in-law, unable to escape. These women were just as much exiles as the banished samurai who came by basket over the river.

So, what kind of music did these people produce? Of course they had their festivals, dances, and celebratory times, it wasn’t all darkness and hard work. Still, one can feel the isolation of the place in the wandering voice accompanied in its melody by the lone side flute, with various drums and samisen to complete the palette. The oldest folk song in Japan, the Kokiriko, comes from this area. It is danced using a unique instrument called the kokiriko or sarasa, composed of 108 pieces of wood which are moved horizontally causing a slapping or whirring sound. The song itself is quite sad and gloomy in tone, but the movements of the dances are elegant. References in the words of this music are often made to loneliness, to the high peaks of the mountains which must be crossed by people taking goods to what must have seemed very faraway towns.

Now I’d like to contrast this with the music I heard in Okinawa. Most people are familiar with the sound of this music, with swinging samisen rhythms, hard-to-understand dialect, and choruses (hayashi) sung by high-pitched women who sound like cats.

The history of Okinawa is very different. It was an independent kingdom known as Ryukyu (Dragon Ball), which dated from 1429, up to an invasion in the 19th century by warlords from Kyushu, and its official incorporation into the Japanese nation in 1879, with full voting rights in the Japanese nation not secured until 1912. In the twentieth century, Okinawa has been the site of US military bases, which has caused dissatisfaction among the native residents.

Culturally, Okinawa is very different from Gokayama, mainly in the roles the ocean and much warmer climate play. I find this evident in the music, which is largely about romance, flowers and birds. It is a beautiful subtropical paradise in the minds of mainland Japanese, but has its own vibrant and old culture. The music may be divided into classical (from the Ryukyu kingdom) and folk (for a long time denigrated as inferior to the classical genre). There is also “new folk” (shin-minyo) which mostly dates from the 20th century.

The most interesting difference to me in these two kinds of music is as follows. As a musician, I am very taken with the differences in the scale used by traditional Japanese music, including Gokayama, and Okinawan music. Traditional Japanese music uses the pentatonic scale, (do-re-me-so-la, or 1,2,3,5,6) which can be heard in some Western folk music (think of the scale used in “Camptown Races”). Okinawan music, however, makes use of other tones (notably fa and ti, 4 and 7) which gives this music a much different feel, somehow warmer and more human, but still alien-sounding from a Western point of view.

My favorite Okinawan song, whose name unfortunately I can’t read, when I first heard it on a Japanese folk music tape in the 1970s, sounded like a journey song, with a slow clopping sort of beat that made me think of horses walking. I was quite surprised when I found that this song is actually about a courtship.

I like the slow, swinging rhythm of these old folk songs, which is very relaxing compared to the music one hears nowadays, with its beat that reminds one of a racing heart. Lovely memories of trips gone by, from the days when one made one’s own trips instead of trying to see what everyone else sees. We didn’t go to the most famous of the Gokayama villages, Shirakawa-go, and also spent sone time on a relatively remote Okinawan island, Kumejima, whose tourist slogan is “The island where you can become zero.” Wonderful. There are so few opportunities to become zero in modern life.

(Much of the historical and cultural information here was taken from Wikipedia.)

header.all-comments