TWO WORLDS AT ONCE

- Rebecca Otowa

- Aug 12, 2024

- 5 min read

(Please forgive the holes in the following two-bit explanation of Buddhist thought. It is mine, culled from various sets of ideas and also my own experience.)

This morning was grave visiting day, and I participated. Our tiny temple’s graveyard has granite tombstones, one for each family of living parishioners, and also older stones that commemorated ancestors long gone by who had one stone each, with the Buddhist name almost worn away, and the little trough for water at the base full of dead moss. Fresh flowers were everywhere, representing either a substantial financial investment at the local supermarket flower shop, or careful husbanding of flowers in the home veggie patch these recent dry weeks, or both. They made splashes of welcome color in the small, gravel-pathed, grey-stone-walled, sunshiny pocket of space where the parishioners stood in a small slice of shade made by the temple building. As it became their turn, they offered incense at each tombstone after the priest, his bald head shaded by a large umbrella (mine), had recited a few well-known passages.

One phrase caught my ear each time – Hyaku sen man go nan so gu (Hard to encounter over millions of years), meaning the teachings of Buddhism, which are available only to some souls in certain reincarnations. I guess it is meant to make us, who are lucky enough to have encountered the teachings, feel grateful and/or privileged. But it also contains a feeling of an exhortation to take responsibility for this. In ordinary religious practice this means doing what is required, like cleaning up and visiting the graves, which are mostly not religious but social or family activities, at least in Japan.

I have long been a spiritual seeker, taking up and picking the bones out of various teachings, notably Buddhism, Christianity, and the Western magical tradition, which admittedly are all vast and contain many different, sometimes contradictory, teachings. I never felt committed enough to hitch my wagon to any of these stars, or to the human beings who promulgated them and were variously known as priests, gurus, or ascended masters, for more than a little while. I have not made a lifetime commitment to any established system, but have found things that “make sense” to me in each one. I remember how glad I was to have found Buddhism, which seemed so cool and unemotional compared to the drama of Christianity. It didn’t even have a deity in its oldest and purest form. There were various principles of living which, when followed, could lead one to a state of mind where one could “rise above” the general suffering of humankind, and either continue toward enlightenment alone, or feel a compassion for one’s fellow beings and a wish that they, too, could be free of suffering.

Broadly, the material world (shiki, meaning color, form, emotion, sex, all the brightly colored things that surround us and seduce us into ever greater suffering) is thought of as opposite to that which lies beyond it, which is emptiness (ku, not really satisfactorily translated as emptiness, but is usually said to be “not this, not this”; in other words, any attempt to describe it beings it into the realm of the material and thus fails), which, when realized, is pure, clean and peaceful. To find this realm is generally called “enlightenment”, and is said to change one’s life.

The Great Vehicle of Buddhism (Mahayana) which is most common in East Asia – Japan, China, Korea, etc. – has a tiny writing known as the Heart Sutra (in the sense of “the heart of the teachings”), which is thought to be a precis of the vast body of writing known as the Sutras of the Great Knowledge. Many thousands of years, and many thousands of human beings, have pored over these teachings and over the little (one-page, relatively easily memorized) Heart Sutra, of which it is generally recognized that the core is Shiki fu i ku / Ku fu i shiki / Shiki zoku ze ku / Ku soku ze shiki (this is the Japanese pronunciation, and roughly means “Form (the material world) is no different from emptiness, and emptiness is no different from form; form is itself emptiness, and emptiness is itself form”).

Two worlds, which we can inhabit simultaneously, and which are fundamentally the same, if this sutra is to be taken at its word. But how can we do this? How to give equal weight in one’s mind to the material world and the non-material world?

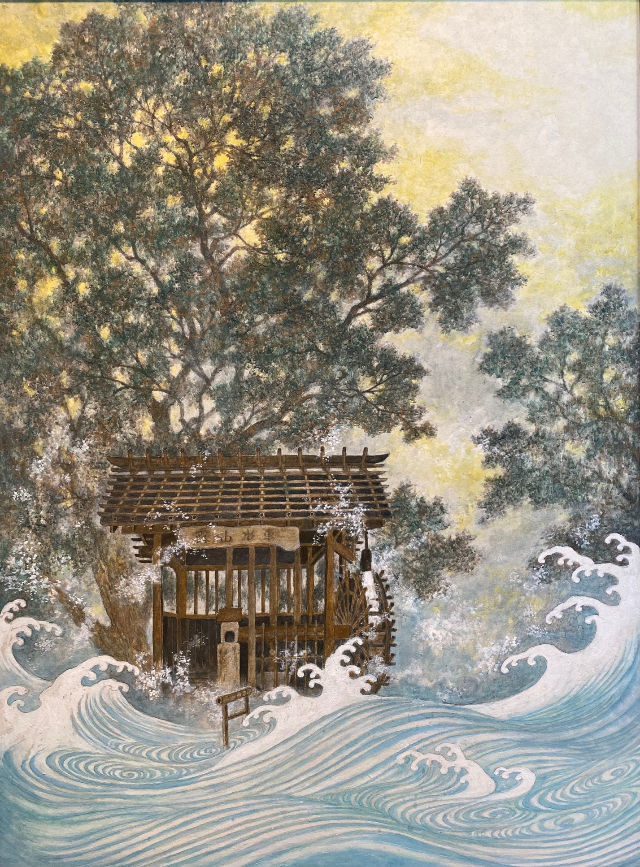

One interesting way to describe this, which uses time as the fulcrum between the two, is the Zen phrase “Before enlightenment – drawing water and carrying wood. After enlightenment – drawing water and carrying wood.” In other words, neither world is a forever home for a spiritual being. If, while living in the material world, you have a flash of what it might be like to inhabit a world of emptiness, to “attain enlightenment”, the next moment you find yourself doing the tasks of a being who inhabits the material world once again. Nothing has changed, and at the same time everything has changed. In one moment you have glimpsed the possibility of being free of this vale of tears; that does change your feelings about the world. But that doesn’t mean you can “escape” from it. It is still there and still has to be dealt with. Ways of dealing with the material world, and the emotions that arise from it, are a very large part of Buddhist writings, probably largely because there is so little that can be said in words about “emptiness”. I often encounter writers who spend lots of words in an effort to describe this other half of the world of our experience, but it is just beating the air in the end. Words are useless, because they are the wrong tools for this job.

So, because we live in the material world, we are weighted toward the experiences of this world. Becoming aware of this other world, and bringing it into our consciousness to the point where the awareness can change our thinking and reactions, is said to be dependent on practice (of certain types of meditation), but I have found that some activities can bring about the same mental state – walking, painting, even napping. Anyone can find some activity where the mind lightens and the ”monkey mind”, which is the problem-solving, forward-moving way of thinking, is stilled.

I am glad that at certain times, I can become aware of this other world. Hitching one’s wagon only to the star of materiality is a recipe for despair, in my view. The awareness of “emptiness” is the leaven that, when remembered, can provide lightness and equanimity which makes it easier to bear the pains, sorrows, or in Buddhist terms, the “suffering” of the material world. Are the two worlds the same, as the Heart Sutra teaches? or when both are present, can they permeate each other to that extent? It is a knotty problem, and like many such queries, doesn’t really have a final answer. The questioning itself is the point.

Comments