WHAT’S IT LIKE AT THE TOP?

- Rebecca Otowa

- Feb 5, 2024

- 5 min read

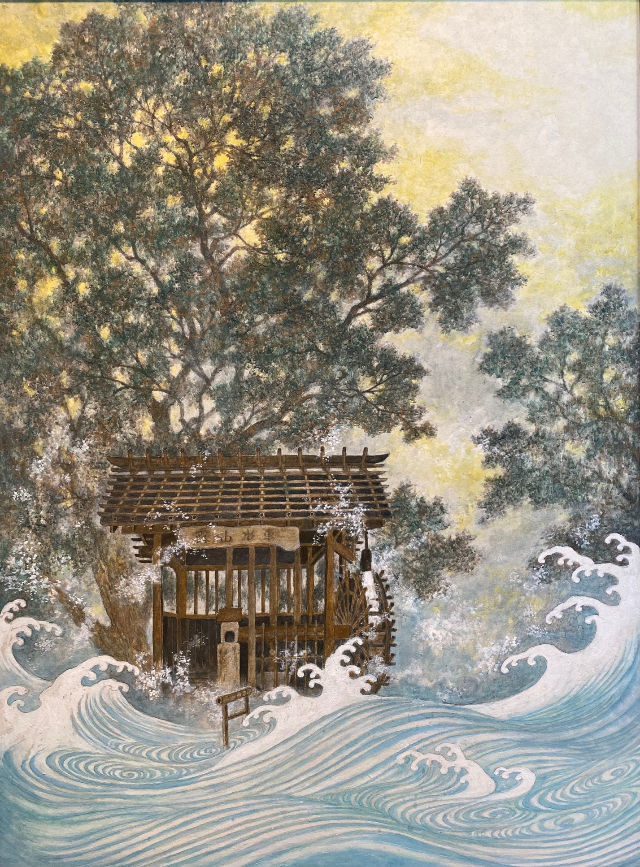

(The picture is an original watercolor painting by me called “The Pilgrim”, 2013.)

Recently I had to ponder a very important issue, which arose from the return of thousands of tourists to Japan and my beloved Kyoto city. During the Covid pandemic, things were peaceful in an almost dreamlike way, but now the numbers are going up again. A recent article in The Observer said that visitors to Kyoto in 2022 “exceeded 43 million – about 10 times the city’s population.” And it is going up all the time.

In response to the article, I made a comment about “armchair travel” and the responsibility of the traveler to think about the benefits he is conferring on a place, instead of only thinking about the benefits to himself. Another person rebutted me, saying that I and other advocates of armchair travel are now older and had plenty of opportunity to travel when we were young, so how can we deny this opportunity to others who are young now? This commenter said that they hoped their grandchildren would never hesitate to take advantage of the opportunity to travel and gain precious experience.

Quite apart from denoting the differences between various types of tourism, and asking such questions as whether a long-term student stay is different, and how it is different, from a few days’ stay for “sightseeing”, there is another much larger issue here. It is that of opportunities that our generation had and whether (and why) these are to be decreased or curtailed now that the world is a little different.

It’s pretty clear that “our” generation (by which I mean the “boomers” -- the post-WWII bunch of kids in developed countries, and those who have been born since then) have known a half-century of relative peace, plenty, hygiene, chances to travel, pain-free generally available medical care, and a longer life span than any human beings before us. We have had it pretty good. Those of us who are alive today in these countries are, in fact, living at the top of the parabola of human experience, and it might be safe to say that no one has ever had such advantages before and no one knows how long this will last, probably not that long if we compare our lot with that of others in history. Many would say that it is all very well for those of my generation to say “Don’t do that” environmentally unsound practice or unhealthy life choice to younger people, as we had freedom when we were young to do these things. (Actually the writing was on the wall even then, but few of us really took it to heart.) It is rather like the Third World countries who, on reaching a certain amount of affluence or influence, are slapped with a bunch of rules about carbon footprints, etc. by First World countries. It seems unfair that the developed countries get to call the shots to other countries, even though only 100 years or less ago, they were doing the very things they now condemn.

But we are all on a continuum, and it is by no means correct to say that we who live in this way, with so many advantages, “deserved” this, any more than it is correct to say that we are to be “blamed” for it. In other words, we don’t know enough about the human condition, on a big picture level, to say or think either one. In this case, should we just enjoy our privileged status, or do we have a responsibility to feel guilty about it? What kinds of things must we do to propitiate someone or something for our advantages? How much is enough? We all know people who have dedicated themselves to some cause or other, have made it their whole lives. We also know people who don’t seem to care one way or the other, who are engulfed in their own life situations and never feel they need to “pay back” anyone or anything for the advantages they enjoy. These people may be personally known to us or they may be public figures. It’s fashionable to “judge” well-known people; and we know how uncomfortable we feel when we judge ourselves (or are judged, in the sense of “you can’t possibly understand my pain”) in situations where, for example, we have escaped big problems such as disease or natural disasters. These things have hit those around us, but not us. This time.

In the view of people from previous ages, it may seem that all of us are ripe for judgment and even condemnation. They would probably think of us as decadent, pleasure-seeking, and free in ways that would seem unthinkable to them. In the light of present circumstances and dangers to the human race, it may seem that earlier people had a much more peaceful and plentiful lifestyle. But even in my lifetime, there was harassment of homosexuals and people of other races, there was enormous social pressure placed on some sectors of society, especially women, there was religious and philosophical persecution, all even worse than now. It seems that the importance of personal responsibility and self-awareness has never been absent from the human condition, but it also seems as if whole sectors of people, even whole nations, were able to sidestep these and tell themselves that what they were doing was right, citing religious works or other things as justification, as they continued to enjoy the lifestyle they had.

When I was a young mother, there was debate over what to do while the baby slept – should one rest as well, or get on with the work that would not be possible when the baby was awake (they were talking mainly about housework I think)? I noticed that the maxim “Sleep when the baby sleeps” came into prominence about that time. If we translate this to the current world situation, the baby may seem to be asleep now, and a lot of us can enjoy a bit of a break from shortages, heartache of war, etc. these days. But what happens when we slip away from the top of the parabola, when the baby wakes up?

I don’t mean to judge people who want an R&R lifetime, or to pat people on the back who have chosen to propitiate by going vegan etc. But it is an interesting question. To what extent do we, at the top, feel that we are here, and how do we justify it to ourselves? And is it “right” to demand responsibility, or accountability, from future generations if we didn’t do these things ourselves? Should I extort the pleasures of “armchair travel” since I had plenty of opportunity to travel when I was young …should I demand that future generations be more aware of their impact on places when they visit them than I was all those years ago?

Is ignorance an excuse? Do I need one? If I am excused by others, can I excuse myself? And what good will it do if I do or don’t excuse myself? It is, I would submit, in our attention to questions like these that we can see big changes in human life -- now there are no corpses lying in the streets, gay people can get married, women can increasingly have the jobs they want that are suited to their character and not to their bodies or what clothes they like to wear. In other words, the action of pondering these questions itself (not necessarily deciding them) is what fuels human evolution. What else?

What do others think about this?

I always tell my kids that parenting was all about DAMAGE CONTROL -- I have zero natural maternal instinct (though fortunately I developed some "on the job") so when I raised them, I just tried doing different things that made sense to me, and some of these things worked while others didn't. And when I screwed up, I had to make it right somehow, and do whatever I could possibly do to mitigate the damage.

The concept of damage control can be more broadly applied to almost anything. Older people can say to younger ones, "Hey, I did THIS, but then this very bad thing happened because of it, so if you want to do THIS, you need to figure…

At first, I thought this was going to be just a cranky rant; it wasn’t, and I tend to concur with you. I think we might have a responsibility to share our thoughts and experiences, if not just to show that we are doing something young people will need to learn to do: reflect on what one has done and correct those actions which need to be corrected. 🙂

History, society, responsibility, human rights, proper use of resources, these are all messy and evolving things. The world is flux, if nothing else. I think that for a person to observe his or her situation as best as he or she can, to try to understand how much that situation is connected to "things beyond," to the degree that he or she can, and try to live the best he or she can in any moment is good enough. Rebecca, just keep painting and writing!